This February, I had a chance to visit Colombia for a school trip as part of an international economic development course at the University of Michigan’s Ford School of Public Policy, where I am a grad student. Our group project focused on sustainable energy, and for it we interviewed a wide range of policy makers, from well-known international organizations to local government officials.

Over the week, the biggest thing that I learned is that we cannot talk about Colombia without a map. If you look at Colombia from numbers, Colombia is a middle−income country with around 50 million population. But if you look closer, Colombia is a combination of many different countries—differences across regions are profound.

Colombia is hardly the only country facing the challenge of inequality. In the US, for instance, studies show that income inequality is rising, middle−class is diminishing, and between 1989 and 2016, the wealth gap between the richest and poorer families doubled.

Boston suffers from the worst income inequality in the United States. A Brookings study mentioned that the top five percent of households in these cities earned income at least 18 times as high as bottom 20 percent of households.

As a public policy major with a strong interest in programming and data visualization, I am interested to know how inequality shapes different neighborhoods, undermines health, and how the pandemic of coronavirus is affecting different portions of neighborhoods.

To understand these questions, we must start with maps.

Income inequality is not just a matter of numbers. When inequality is examined at a level as granular as census tract (comparing differences among small slices of neighborhoods) it reveals deeply relevant impacts for individual families and their children. For example, one study suggests that children in low-income families who moved from Manhattan to Hudson County, NJ, when these children were born earned 16% more as adults on average in 2015 than demographically similar children whose families stayed in Manhattan. The New York Times also reported in 2018 that poor children from Seattle’s 115th Street went on to households’ earnings about $5,000 less per year than children from families at the same income level raised in Northgate—a mere five minutes away.

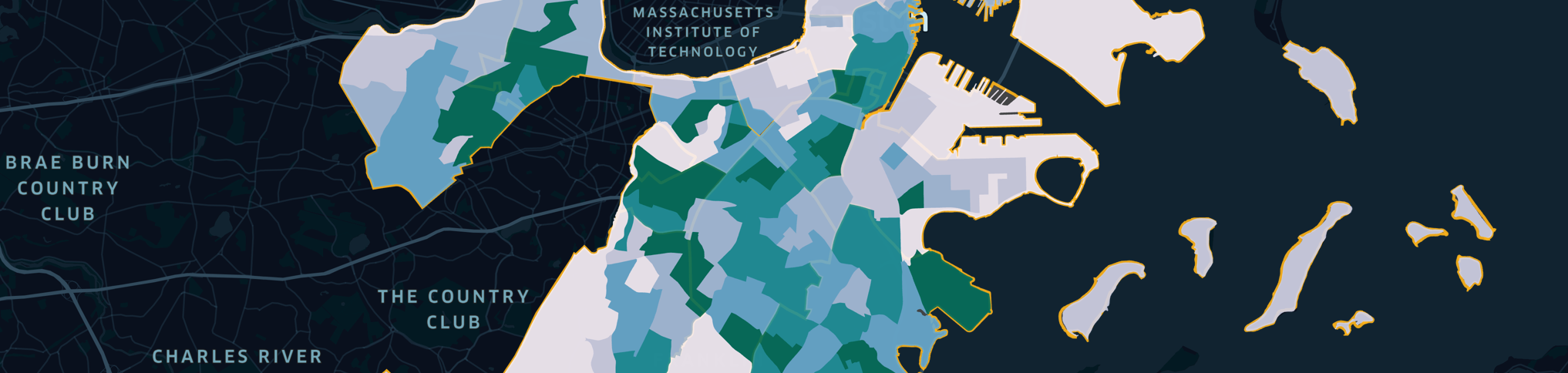

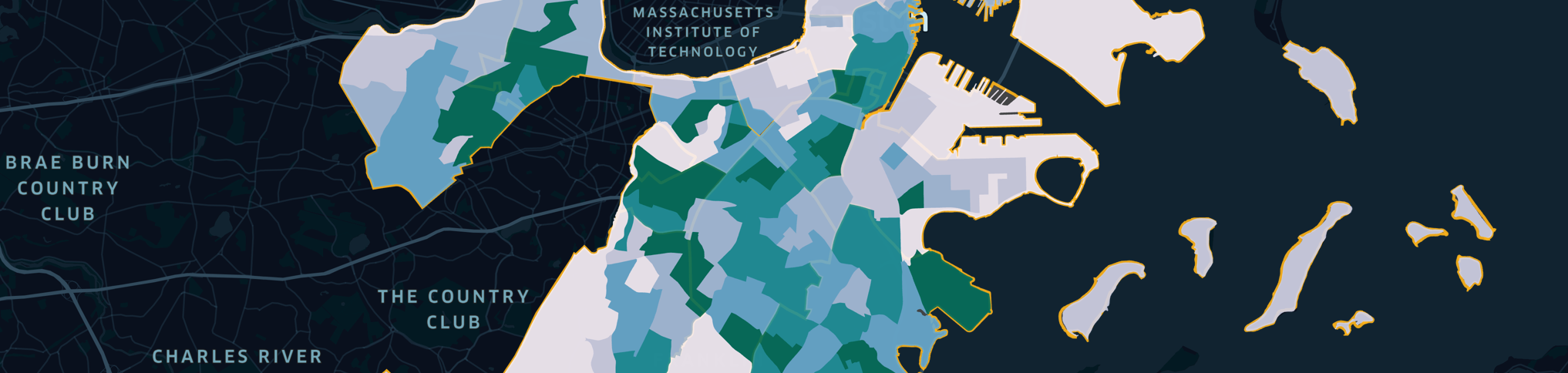

What about Boston? Here is a map that shows the net difference between median household income in 2017 and 2019:

As we can see from the map, median household income increased in most places in Boston from 2017 to 2019. But even within the same neighborhood, some census tracts are considerably better off than others. The scatter plot below gives you a clearer picture of the changes of income overall. Feel free to brush the scatter plot and explore the changes.

Take a look at Allston. The neighborhood is known for its proximity to universities, such as Boston University, Boston College, and Harvard. Allston’ busiest area is the triangle—shaped intersection where Harvard, Brighton, and Commonwealth Avenues meet. Everything that students love—from bars to concert venues, from Asian hotpot to traditional American diners—is located here.

But census track 8.03, located slightly above Allston, showed a serious decline in median household income from 2017 to 2019. Based on ACS 2018 data, 28.2% of people in that census tract live below the poverty line.

Another example of sharp income disparities within small urban areas is the stark comparison between two closely located census tracts in South End: census tract 704.02 (around Herald Street) and 703 (only 0.6 miles away, around Appleton and Columbus Streets).

In 2017, the median household income of census tract 703 was $112,500, more than two times higher than that of census tract 704.02. But from 2017 to 2019, median household income continued to increase in the richer area, while slightly decreased in the poorer census tract.

Research has shown that social indicators such as income are closely linked to health. By the numbers, Massachusetts is a national leader on healthcare. The state has the highest rate of insured residents, high life expectancy, and 314.8 doctors per 100,000 people.

But not all neighborhoods in Boston share the same health statistics. A 2015 study shows that life expectancy varied greatly between neighborhoods only a few miles apart. For example, life expectancy in Roxbury is 58.9, but as high as 91.9 in Back Bay.

Massachusetts MassHealth (Medicaid) provides health insurance coverage for low− and middle−income households, but eligibility depends on a wide range of factors, such as age, disability, income, and residency. Although Massachusetts has achieved a low overall uninsured rate, a high number of uninsured people live in Boston. From the map below, you can see that the uninsured population is predominantly concentrated in neighborhoods with low median household income.

Another study shows that 42.5% of the uninsured are noncitizens,and most were either unemployed in the past years or only worked part−time, making it unlikely for them to be able to afford private health insurance without financial assistance. Other barriers lie in the health insurance application process, itself. Many uninsured Bostonians have limited English proficiency, lack home internet access, and so on.

Take a look at the central square in East Boston, which includes census tracts 502 and 507.

These two census tracts have almost identical demographics: similar median age, population number (around 5,600), race breakdown (21% white, 69% Hispanic), and foreign-born population rate. But in census tract 507, 24.6% of the population lives below the poverty line and around 500 people are uninsured, while in census tract 502, only 13.9% live in poverty and around 189 people are uninsured. I am not exactly sure what accounts for the difference between these two neighborhoods, but it seems notable that census tract 507 is closer to a grocery store, while the more affluent 502 is closer to a daycare center and far more small restaurants.

Unfortunately, this is not the end of our story. Coronavirus is hitting people in poverty the hardest. The timeline below shows a series of coronavirus related events in Boston

The differences across neighborhoods matter more amid the spread of coronavirus. Even before the spread of coronavirus, research has shown that anxiety and stress resulting from living in poverty gives poor people little mental “bandwidth” to perform everyday task because they have to deal with numerous worries that eventually ”burn up their cognitive capacity”. The map you see below is a combination of a dataset provided by CDC and Data USA. You can see that in 2017, median household income is highly correlated with the percentage of population that experience mental health issue longer than 14 days:

As coronavirus spreads across the globe, it deepens inequality. Many low-income residents could not afford to stay in safe, stable, and controllable environment, while those who are wealthier can stay at home and limit their exposure to coronavirus. In addition, people in certain industries are more likely to get sick. For example, in Massachusetts, there are now 24 workers from Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority tested positive for COVID-19. Among them, more than half are bus drivers, the others include train drivers and inspectors.

Boston announced its first confirmed case of coronavirus on February 1st. On March 15th, Mayor Martin J. Walsh announced the Boston Public Health Commission (BPHC) declared a public health emergency in the City of Boston. In the charts below, I compare reports of non-emergency services in January, Feburary, and March this year with previous years (2017, 2018, and 2019). You could see that number of non-emergency reports are relatively the same in January and Feburary. But in March 2020, the number of reports significantly decreased.

To read more about confirmed coronavirus cases in Boston and Massachusetts, you can click here.

As of April 8th, there are 16790 confirmed cases of coronavirus in Massachusetts and among them, 3600 are from Suffolk County. I would really want to see the race and ethnicity of those who test positive, but just a third of the data is available, and only 133 of the total 433 deaths had a race or ethnicity listed. (Read the story here)

Based on limited data, the death rate of coronavirus mirror to Massachusetts’ overall racial breakdown: 74% deaths were white non-Hispanic, followed by Hispanic (11%) and Black African American (5%). But in cities like Chicago , black residents are dying at a much higher rate. For instance, in Chicago, about 68% of the city’s deaths have involved African Americans who make up only 30% of the population. In Michigan , African Americans make up about 14% of its population, but 40% of all coronavirus deaths.

The website is about getting close to poverty and inequality. I hope that data and visualizations could pause you a second, break your heart a little bit, and then if you have a chance to contribute, do not forget the maps and the people that have to deal with the mundanity of social inequality.

This website could not be possible without support from my instructors and friends.

For my professor Mattew Kay, thank you for teaching me design theories, altair, meeting with me outside of your usual office hours, and sharing photos of your cute cat, Kitty.

For my writing instructors Alex Ralph and Beth Chimera, thank you for helping me piece together the whole storyline.

For my mentor Ben Daniels, thank you for always being so generous with your time and inspiring me to become a better thinker and programmer.

I had some really stressful moments in March and April. But thanks to friends from Gregory Co-op house, especially Marina, Tanvangi, Mariam, Katherine Cima and Jocelyn Kuo from the Ford School, and my “werewolf squad” I was able to live without too much worries.

And thank you, my dear reader, for reading this webpage. If you have any comments or feedbacks, please do not hesitate to drop me a message via: linglp@umich.edu or connect with me on LinkedIn